|

The New York Times, March 12, 1944

HOW JACOBOWSKY MET THE COLONEL

In

Which the Writer Explains a Comedy About A Tragedy

By S. N.

BEHRMAN

In Hollywood one evening M the spring a 1941 I was invited

to dinner by the late Max Reinhardt to meet Franz Werfel.

Some months earlier I had read in The New York Times an item

to the effect that Mr. Werfel had been captured by the Nazis

in France and killed. His publisher, Mr. Huebsch, told me

that all efforts to reach Werfel, even through the Red

Cross, had been unavailing. He had tried through every

conceivable agency. He could find out nothing about him and

there was nothing further he could do.

|

|

|

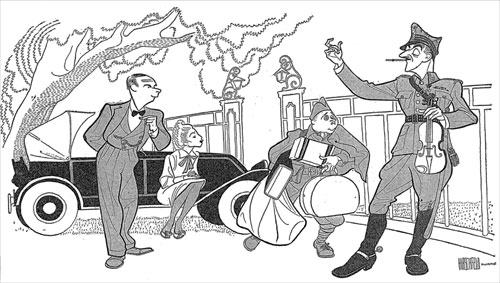

Some of the folks who will be seen in the Franz

Werfel-S. N. Behrman comedy, "Jacobowsky and the

Colonel," that comes to the Martin Beck Theatre

Tuesday evening. In the usual order: Oscar Karlweis,

who is Jacobowsky; Annabella, J. Edward Bromberg and

Louis Calhern in the colonel's raiment. |

Here, at Max Reinhardt's dinner table, was the escaped

victim, cherubic, forcing himself to talk, out of courteous

deference to me, an ersatz English, and recounting the long

story of his exaggerated death. I had met many refugees,

great and small, and from all of them I had heard an account

of their experiences. But this was something new in horror

stories. For Mr. Werfel, talking with a gusto unhalted by

the idiosyncrasies of English syntax, his blue eyes

gleaming, kept the table amused and spellbound for well over

an hour.

I have never heard nor ever read an account which gave me an

idea so vivid of what it meant to be in France in that

summer after her fall, a step ahead of the Nazis: the

frantic crowds in front of the consulates, the pulverization

of the consciousness into one acrid grain of desire—to get a

stamp on a piece of paper. "Our blood," said one of the

characters in the play that came out of this evening (that

is, he said it until the line for some forgotten reason was

cut!) "is the ink on visas." Werfel described one scene

which I shall never forget. We meant to get it into the

play, but couldn't; perhaps one day it will be in the film

version.

In Fallen France

A frantic polyglot crowd is milling about in the hot sun

before the consulate of a little town in the south of

France. The badgered consul is sitting before his desk, a

little mountain of passports before him. For days he has

been answering questions, making life-and-death decisions,

stamping papers. The room is clammy in spite of the sun

outside; a fire burns in the grate behind him. The line of

applicants reaches from his desk to the square outside. A

Czech traveling on a Polish passport or maybe a Pole

traveling on a Czechish is before him. He weaves about in a

labyrinth of technicality. Suddenly, lost in it himself,

blinded by it himself, trapped panically in an unnamable

claustrophobia, he is seized with a maniacal impulse for his

own freedom. He seizes the pile of passports on his desk and

flings them into the fire. The papers burn to ashes, as do

the hopes of the unfortunates whose names were on them.

Among the anecdotes Werfel told was one which became fixed

in my mind because of some peculiarity of compactness. A

Polish-Jewish business man buys a car from a rascally

chauffeur. Having bought it he is faced by his inability to

drive it. Happens along a reactionary Polish colonel who can

drive.

The colonel consents to drive the refugee's car to the

coast, first throwing out from it all of his possessions,

substituting his own. This seized me at once. There came

irresistibly into my mind the pattern of one of my favorite

plays, "The Front Page," by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur.

A Play Begins

Werfel went on weaving his farcical phantasmagoria—for when

the conventions of property, justice, the divisions of life

and death are all held in abeyance by an arbitrary god, the

habits based on these conventions evidently jumble into

farce like a macabre Alice in Wonderland—while I kept

thinking: "Two men in an ambivalent relationship—two men

from the opposite ends of the earth—opposites spiritually,

physically, mentally—held together during a flight by a

common enemy and a mechanical thing—they hate each

other—they part—they miss each other. . . ."

After dinner I went to Werfel in the living room. I told him

that I thought that in this story of the Polish refugee and

the colonel there might be a comedy. It seemed simple and

natural; it seemed to fall out into beautiful folds like a

fine linen sheet when you shake it a bit. We stood around

there in Max Reinhardt's drawing room shaking it around a

bit. It is curious that in spite of the creative trek this

play has taken in the intervening three years its main

outline is the same that it assumed that evening not ten

minutes after Werfel had finished his tragi-comic odyssey.

Some Questions

How is it that one of the greatest tragedies in history

should seem funny on the lips of one who had acutely

suffered it? To answer this one would, perhaps, have to

command an ultimate psychology. Why, in exile, do Ernst

Toiler and Stefan Zweig kill themselves, while Franz Werfel

settles down in the same exile to write "Embezzled Heaven"

and "The Song of Bernadette"? Why does Virginia Woolf throw

herself into a lake, while the speeches of Winston Churchill

twinkle with an ineluctable humor. They all saw the same

sights, endured the same privations, were faced with the

identical dragon. Is humor the amalgam of resilience in

adversity? And yet many of the saints and martyrs lacked

humor whatever else they possessed. Perhaps humor is the

salt of survival and the lack of it the hemlock of

martyrdom.

In the pre-New York tour of "Jacobowsky and the Colonel"

several of the critics gave the effect of rubbing their eyes

at the phenomenon of watching a story essentially tragic and

nevertheless enjoying it. The great scene of Shaw's "Saint

Joan" is "full of laughs" while the subject under discussion

is the exact judicial and spiritual justification for

burning Joan at the stake. The "comedy relief" in

Shakespeare's tragedies does not offer the asylum of analogy

for in this play the comedy (let us hope!) is not

interlarded—the point of view on the whole tragedy is comic.

Must one apologize for this? If man is the only animal who

can laugh, need he apologize for his distinction? I can only

say that Werfel, a profound mystic as his books show, made

us all laugh on that spring evening at Max Reinhardt's. None

of us felt therefore that he had suffered less or felt less. |