|

The New York Times,

June 2,

1968

At 75 S. N. Behrman, Speaking as a Survivor, Not a

Contemporary, talks of many things, but principally of

people he misses and of war and peace

By S. N.

BEHRMAN

One morning you wake up and, with no encouragement whatever

from anybody, find yourself 70. I am so inured to the

Biblical tradition in which I was brought up that I felt

that the very next day was already an overdraft. You never

think, when you are younger, in terms of decades—you are too

busy—but this particular numeral is peremptory. In a week

(D. V.), I shall wake up to 75, but I am by now so overdrawn

that I am grooved for it. Samuel Goldwyn's hilarious remarks

have been quoted all over the world for 50 years. It is

pleasant now to set down a profound one. Ira Gershwin met

Goldwyn, who is well over 80, at a party recently and

complimented him: "You're looking very well, Sam." "What

good does it do?" said Goldwyn.

In the fancy synagogues, the deceased of each week are

described as having "received the summons from on high."

They make it sound like a telegram from the boss offering a

vacation with pay. The poignant aspect of it is that almost

every morning, when you open The Times, you are made

conscious that you are not a contemporary but a survivor;

you are forced to say an unpremeditated farewell to a

vacationer.

In London, in 1946,I had dinner with Somerset Maugham in his

suite at the Dorchester. He said: "Whenever I come back to

London, the first thing I do is to look at the obituary

columns of The Times. I know that one morning my name will

appear in those columns, but I don't believe it!" It is

exactly true of all of us, and rightly so. Speculations

about the "next world"—is it next or is it antecedent? —are

useless because they are acts of life. It is like trying to

imagine what it is to be a rock. When it does happen, it

won't be to you that it happens because you will be gone.

You will exist only in the memories of the few who knew you.

It will always be a few, even in the case of the most

eminent. Take the most prestigious historian of 16th-century

London. He can give you only a marginal account of those who

lived in 16th-century London, only of those who achieved

notoriety in it, its rulers and its poets. The rest will

remain forever anonymous. History is for the articulate.

Sometimes the dying are articulate. In his remarkable

biography of Lytton Strachey, Michael Holroyd quotes

Lytton's last remark: "If this is dying, I don’t think much

of it.”

The other day I read that Edna Ferber had died. I knew her

intermittently over a period of many years and never well.

Her obituary evoked in me a single memory and it made me

smile. I was having tea in his apartment with George S.

Kaufman. Edna came in, harried. "Oh," she said, "I had the

most terrible nightmare last night, really horrible. It's

made the whole day hideous." We inquired. "I dreamt," she

said dramatically, "that I was a wallflower at an orgy!"

Sometimes these intelligences open long corridors and wring

you. Last September The Times struck me in the face with the

announcement that the English poet, Siegfried Sassoon, had

died. It opened a long corridor, from the day I met him in

1921 to the last letter I had from him, a year ago. I had a

job on The Times Book Review. The editor, Clifford Smyth,

sent me to interview Sassoon, who was here on a lecture tour

to read his war poems. I didn't have far to go: Siegfried

was staying in Westover Court, which used to be behind the

Putnam Building on the site later occupied by the Paramount

Building. In a book published 30 years later, "Siegfried's

Journey," Sassoon described the extra illumination he got in

his rooms from a vast sign atop the Putnam Building: " . . .

my nocturnal outlook was dominated by the Putnam Building,

above which blazed the electric sign of Wrigley's Spearmint

Gum. Flanked by two peacocks whose tails were cascades of

quivering color, about a square acre of advertising space

contained the caption, 'Don't argue but stick it in your

face.' "

Westover Court was a very unlikely place to find in New York

even then: four stories high, built around a court with a

tree in the middle. On winter nights, when you came home

late, the bare branches of this tree would be covered with

night birds who resorted to it in lieu of a forest. Westover

Court was a bachelor establishment with two-room apartments;

it was like a dormitory in a New England college. Actors and

artists and singers lived in it. The telephone in the hall

leading from 44th Street was presided over by the McGraw

sisters, who took turns. They knew all the secrets and kept

their mouths shut.

|

|

|

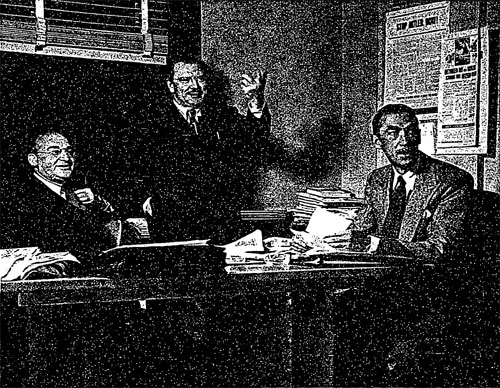

GREAT DAYS—Behrman, left, in 1940 with Maxwell

Anderson and Robert E. Sherwood during the run of

Sherwood's Pulitzer prize-winning "There Shall Be No

Night." The play, inspired by the Russian invasion

of Finland, had been staged by the Playwrights'

Company, founded by the three gentlemen shown plus

Elmer Rice and Sidney Howard. |

I can’t remember the interview I did with Sassoon for The

Times Book Review; it couldn't have come to much, but the

talk I had with him on that first meeting did. It led to a

friendship that lasted for more than 40 years. He told me

his story. The war poems were so bitterly antiwar that their

publication led to a Parliamentary inquiry. Sassoon faced

court-martial. What made the military scratch their heads in

bewilderment was the perplexing fact that Sassoon's war

record was recklessly heroic. He had been cited for bravery.

But there is nothing beyond the military mind; it came up

with a solution: that Sassoon was crazy—they called it shell

shock. He was sent to a lunatic asylum. Had it not been for

the accidental presence there of a great man, Dr. William

Halse Rivers—a famous English psychiatrist and

anthropologist for whom Sassoon's duality as war hero and

pacifist was not in the least paradoxical—he should never,

Siegfried told me, have survived that experience.

I saw him constantly the rest of the summer and went to many

of his readings. Sassoon was tall and lithe and

extraordinarily handsome. He read quietly, without "effect,"

without inflection. I remember the stunned silence that

followed the reading of one poem at the Free Synagogue in

Carnegie Hall. I copy it from the little book of his war

poems that he left me when he returned to England:

DOES IT MATTER?

Does it matter? —losing your legs? . . .

For people will always be kind,

And you need not show that you mind

When the others come in after hunting

To gobble their muffins and eggs.

Does it matter? —losing your sight? . . .

There's such splendid work for the blind;

And people will always be kind,

As you sit on your terrace remembering

And turning your face to the light.

Do they matter? —those dreams from the pit? . . .

You can drink and forget and be glad,

And people won't say that you're mad;

For they'll know that you've fought for your country,

And no one will worry a bit.

I found out not long after that Sassoon was lacerated by a

private agony. What made his situation intolerable was that

he had the time to brood over this agony. He explained that

when he got the idea for a poem it took him very little time

to write it. But how could he forget when the anodyne of

creation had worn off? I recalled a remark of Copey's—Charles

Townsend Copeland's—in English 12 at Harvard: that poets

wrote the best prose. I nudged him toward trying prose. I

still have some pages, in his beautiful handwriting, of a

novel he began that summer, which he never completed. The

prose project kept our correspondence alive after he

returned to England. The eventual result is an exquisite

classic: "The Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man."

Some six years after I met Sassoon in Westover Court, I

became a trans-Atlantic traveler myself and I often stayed

with him in various houses, including Heytesbury House, in

which he died. Staring at the sensitive face of the young

Sassoon in The Times, as the memories crowded in, I found

myself again smiling. On my first visit to London, Sassoon

took me to see Sir Edmund Gosse. Gosse was perhaps the last

of the great Victorians still living in London. He was of

medium height, compactly built, with gray hair parted in the

middle. He wore a black patch over one eye. I discovered

later that he shifted this patch from eye to eye, according

to mood, thereby anticipating an advertising genius by about

50 years. It was February; I stood shivering in the icy

hall. Sir Edmund noticed this. "Our guest is cold," he said.

"We must go into the library." The difference in temperature

that was perceptible to Gosse was imperceptible to me: I

shivered in the library.

Gosse had a booming voice; his sentences were beautifully

designed; he took pleasure in pronouncing them. He was

delighted with a method he had discovered a week before for

getting away from an evening party at Buckingham Palace. "I

took Lady Gosse by the arm," he said, "and started her on a

round of admiring the pictures. We toured the room, admiring

each picture, until our tour led us to the entrance doors.

We walked through these with the abstracted air of art

lovers on the quest for still more bounties. Isn't it

ingenious?"

Gosse never stopped talking, Siegfried punctuating here and

there with appreciative exclamations. Sassoon must have

felt, finally, that I was being left out of the

conversation. He made an effort to admit me.

"Mr. Behrman," he said, "has a play in London."

Gosse made a show of interest.

"Ah," he said. "Really? And who is in it?"

"Noel Coward is in it!"

"Ah! Noel Coward! That young man!"

"Do you know him?"

"Certainly I know him. I met him at dinner at Sir James

Barrie's."

Somewhat satirically, Sassoon said: "Was he nice to you?"

"Nice to me! Why he fluttered round me like a butterfly

around an OAK!"

The next time I went to England, Sassoon told me of another

visit he had made to Gosse. Lady Gosse had just died. It was

a radiantly happy marriage which lasted over 50 years.

Sassoon went to pay a condolence visit. He expected to find

his old friend depressed; on the contrary, he was in great

form, exuberant. He jumped up from the sofa when Sassoon

came in.

"Ah! Siegfried! It does me good to see you. 'The thoughts of

youth are long, long thoughts.'"

Sassoon said he was pleased to find him in such good

spirits.

"At my age," said Gosse, "death becomes such a commonplace

that you can't take it seriously."

The last time I saw Sassoon was in Cambridge, England, in

1952. He had just come from hearing Robert Frost, and he

said that he was so moved by Frost's reading that his eyes

filled with tears. That notice in The Times permitted me to

do very little else that day but remember. I browsed among

the books Siegfried had given me. One was a charming book of

drawings: "Sketches Near Salisbury." I had come to spend my

last night in England in a cottage Sassoon had taken near

Salisbury. The next morning he drove me to Southampton when

I boarded the Queen Mary. The book, inscribed to me, is

dated:

Fitz House - 23-4-32

On Shakespeare's Birthday

Off to catch the boat

Siegfried Sassoon was one of the few men I have known who

had the attribute of nobility.

I was telling the editor of a local magazine the other day

about the frustrating difficulty I had getting a job after I

graduated from Harvard in 1916. He said that it was very

different now. "Anybody with any talent at all," he said,

"is snapped up immediately after they graduate and often

before they graduate. Often, they're put in jobs which are

much too big for them." He told of one young man who was

made book editor of an important magazine. He felt himself

that he wasn't equipped for the job, but the managing editor

insisted.

I have a single, vivid memory of the June day when I sat in

Soldiers Field in Cambridge waiting for my degree. It is of

John Singer Sargent, magnificent in his scarlet robe and

bright yellow, nicotined mustache and beard, who rose to get

his honorary degree, pinned on him personally by Abbot

Lawrence Lowell. After Sargent and I got our degrees, I was

assailed by a problem which, I am sure, did not bother

Sargent, but which had for years been eroding me: what to do

next? It took me 11 years to find out. I tried everywhere to

get a job, went to every newspaper in New York and even to

Philadelphia and Baltimore. I had some plays, but I was

allowed to keep them. In desperation and financed by my

older brothers, I went to Columbia to get an M.A. in

English.

I took a seminar course in 19th-century French drama with

Brander Matthews. He was a tall, thin man with rather wispy

mutton-chop whiskers. He was an established

man-of-the-world, easy and anecdotal, the friend of Mark

Twain and William Dean Howells, in fact of everybody whom

most people didn't know. We read a lot and heard a lot about

the two most popular French playwrights of the 19th century,

Scribe and Sardou. As an example of Sardou's skill as a

technician—or was it Scribe's? —how quickly and easily he

could establish his leading character as a sophisticated

worldling, Matthews drew attention to a restaurant scene in

which the protagonist enters and says casually to the head

waiter, "Good evening, Henry." This established, so

dexterously, that the hero knew his way around expensive

restaurants.

He told us a lot about the bitter rivalry between the two

playwrights. When Sardou was dying—or was it Scribe?—the

doctor said to him: "Pouvez-vous siffler, Sardou?",

and got the prompt reply: "Pas même siffler Scribe."

He explained that siffler meant to breathe and also

to hiss in the theatre.

One day I made the mistake of bringing into the small class

a copy of The New Republic. Matthews looked at it and said,

"I am sorry to see you wasting your time on that stuff." He

was a stanch Republican and a friend of Theodore

Roosevelt's. Still, Matthews was a kind man. He gave a

classmate and me cards to visit the Players' Club, which

thrilled us, and me an invitation to hear Henri Bergson

lecture in English. I was startled by the immaculateness and

the decorum of Bergson's English. When I reported this to

Matthews, he said: "It is the English of a foreigner who

doesn't know English only the English classics."

The M.A. degree gave me a leg up. I got a job on The Times

typing up and classifying the want ads. The hours were from

3 in the afternoon to 3 in the morning. I worked on the

widest machine I had ever seen; it was like driving a truck.

It was safe and lovely to walk to my room on West 36th

Street at 3 in the morning. I can't remember how it

happened, but from the third floor I crept up to the 10th

and got a job with Smyth, the editor of the Book Review. He

was a kind man, and after a few months he put me in charge

of the Queries & Answers column. The flood of queries about

obscure Middle-Western poets began to bore me. I got the

bright idea of sending myself inquisitive letters. "What has

become of Ambrose Bierce?"

It turned out that Queries & Answers was Mr. Ochs's favorite

column. He liked the obscure Midwestern poets; he found

their view of life uplifting and salvationist. He put an end

to my fascinating correspondence. The tenure I didn't have

lapsed. I was confronted by the same question that hit me

the day John Singer Sargent got his degree: "What to do?"

There were compensations, though not monetary, on The Times.

I got to know E. M. Kingsbury, an editor. H. L. Mencken said

that the best writer in America had never had his name

signed to anything. He meant E. M. Kingsbury. We used to

meet in a bar on 44th Street after work. He suggested a

game. He would say the first line of a poem; I was to follow

up with the next line. The first one to get stuck would pay

for the drinks. "When the hounds of spring are on winter's

traces . . ." Kingsbury's scent—as well as his memory—was

much keener than mine. I paid for the drinks. But these

losses were recouped in more lasting ways. E. M. Kingsbury

was one of the most erudite and delightful men I have ever

known. I went to see him many years later in his office at

The Times. We had a warm reunion. We went to the bar; we

resumed the game. Yeats this time. Kingsbury won.

The Harvard I knew was idyllic. For years I used to dream

that I would wake up in Weld Hall. I still dream it

occasionally. About 10 years ago I was invited to spend a

week in Kirkland House, "to talk to the boys." I wished that

they would talk to me, but they didn't. I expected to be

needled, which would have been fun, but not at all; they

were respectful.

The difference between the Cambridge I had known and the one

I saw now was the difference between a small, manageable

town and a swollen segment of the Boston-Washington

conurbation. Exotics crowded each other in the streets—town

and sari. Headmasters complained to me about the

difficulties of finding apartments and the astronomical

rents. Cambridge, I was told, was overcrowded and had become

a very expensive place to live. I met Dr. Gaylord P. Coon,

the senior college psychiatrist. I told him that in my day

we had the Infirmary; that I had once spent two blissful

weeks there getting over the flu, but that we had no clinic

for psychiatry. I asked him how it was that we got along

without it. Could it be that the proliferation of Freud's

ideas and the creation of the profession of psychoanalysis

had stimulated the profusion of disease? He said he didn't

think so. The need had been as great in my time, but the

afflicted, not knowing where to turn, had kept their secrets

to themselves.

In any case, he was hard put to it to take care of the

undergraduates who came to him daily. He introduced me to a

new category: the Icarus-afflicted, and two classes in that:

vertical and horizontal. Marathon runners, messengers in

plays—horizontal; high divers, chronic fantasists—vertical.

The discussion started with Dr. Merrill Moore, whom we both

knew. He was Eugene O'Neill's doctor and a marathon

sonneteer; he wrote sonnets by the thousands. Him, Dr. Coon

classified as horizontal. I was fascinated by Dr. Coon's

account of how he had, daily, in his variegated and cunning

disguises, to circumvent Icarus. I got a lot out of that

week at Kirkland House. Dr. Coon talked to me, even if the

students wouldn't.

Should the summons come abruptly and should anyone bother to

make note of it, the memorialist might say: "His last years

were overshadowed by the Vietnam war." It is so. This war,

which has extinguished so many lives, has darkened mine.

People are encapsulated in fear, and many serious

commentators doubt the durability of our political system. I

have lived through many Presidencies and heard many

Presidents and near-Presidents. When I was a boy in

Worcester, Mass., I wandered into Mechanics' Hall to hear

Dudley Field Malone booming an introduction for Woodrow

Wilson. It was a noon meeting and hardly anyone was there. I

was there because it was the Day of Atonement and I had an

hour off from the Providence Street Synagogue. This windfall

came to me because they were intoning the prayers for the

dead and those whose parents were still alive were not

permitted to remain. Malone—without meaning to—sounded like

Hubert Humphrey. His barrage was followed by a dissertation,

measured and uninflected, by Woodrow Wilson who, without

meaning to, sounded like Senator McCarthy.

In the same hall I heard Eugene Debs at a meeting also very

poorly attended. I have never forgotten his appearance, his

fervor, his eloquence. No speaker I have ever heard gave

such a quick sense of genuineness. I am sure he would have a

great following if he were alive now. I heard William

Jennings Bryan. He was, oddly enough, intentionally funny.

He spoofed his own attempts to win the Great Prize. He told

of arriving at a South American port on a gunboat. He was

greeted in the harbor by a salvo of cannon shots. It sounded

to him as if it had the makings of a Presidential salute. He

began to count, breathlessly. He counted up to 21. "But," he

lamented, "they went right on firing."

I am a registered Democrat. I've voted for Democrats all my

life. (I defected only once to vote for John Lindsay. My

vote is powerful; my man made it.) In due course, I voted

for Lyndon Johnson. There was, in any case, no real choice.

How odd that a democracy of 200 million people should be so

rigid in its political habit, so unproductive and

unimaginative, as to confront us with the choice it gave us

in 1964.

I remember the distress with which I watched the Republican

convention on television. Governor Rockefeller was howled

down by the Goldwater mob in the balcony. He gave up finally

with the wistful remark: "After all, this is still a free

country." It wasn't at that convention. Goldwater's infamous

remark—"extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice . . .

moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue"—which he

later tried to explain away with his customary ineptitude,

was the pivotal sentence of his speech. He waited to deliver

it and got the howl of approbation he knew it would get.

Then came Johnson and the escalation of the Vietnam war, the

repudiation of his own arguments against Goldwater. Our

leaders lie to us and betray us. It is the sense of this

that is behind the alienation of the young.

I quite agree with W. H. Auden when he says that writers

have no special qualification for passing judgment on

political matters. I agree, too, with Mary McCarthy, who

says in effect that even the most distinguished writer

wouldn't have the competence to be mayor of, say, Sandusky,

Ohio. In Sanche de Gramont's "Epitaph for Kings" I see a

quotation from Louis Madelin: "The French Revolution was

caused by a group of writers who believed themselves to be

thinkers." I agree with all three of them. Still, in spite

of my occupational handicap, I am after all a citizen and a

voter. I can't help having opinions. And I know what I

dislike. I have never disliked anything as I do the Johnson

Administration and the image of Johnson himself as projected

in his public utterances. He has befogged the country in a

miasma of cant. Eisenhower pulped the language; he made a

mollusk of it, spineless and faceless. Johnson has

brutalized it. "Nervous nellies." Could this be addressed to

parents who do not want their sons to be killed or mangled

in Vietnam? "Hang up the old coonskin." At what cost? "Does

it matter losing your legs?" To say nothing of your life.

Now we are confronted by Mr. Humphrey. If I am right in

believing that the country—certainly the young—seethes with

moral revulsion of this war, then what on earth is the sense

of considering as Mr. Johnson's successor a man who has for

four years collaborated and propagandized for that war? The

political columnists tell us, in extenuation of Humphrey,

that he never liked or believed in the war. In what

category, humanly speaking, does this leave him? No.

Evidently Mr. Humphrey would rather be Vice President than

right.

The unfeeling sentimentality with which our bigwig

politicians talk to the people passes belief. As reported in

The Times, Hubert Humphrey pressed hard on the pathos pedal

in a speech in Wisconsin. He described the tears in the

President's eyes when he spoke of the ordeal faced by his

sons-in-law, who were going to Vietnam. Didn't it occur to

Mr. Humphrey that the direct implication of this is that the

President was moved to tears by the war only when it came

close to home? Can it be that Mr. Johnson is a "nervous

nelly"? The great reassurance, the cleansing wind, has been

the emergence of Senator McCarthy. He was the first to stand

up and be counted. He is courageous. The rallying to him of

the young and their improvised effectiveness is thrilling. I

am hoping against hope that I will be permitted to vote for

him.

In the last years another reassurance has unexpectedly come

my way. Seven years ago I was elected to the Board of

Trustees of Clark University in Worcester, where I had been

an undergraduate for two years. I never found out properly

what a trustee is supposed to do. I once asked Dr. Abram L.

Sachar, the president of Brandeis. He said: "A trustee is

supposed to do what the president wants." This didn't help

me because Howard B. Jefferson, then president of Clark,

never asked me to do anything. He explained to me once the

plight of the small college. "The technical colleges," he

said, "can get plenty of money. You can get anything for

science. But a small liberal arts college like Clark,

devoted to the humanities, has tough sledding."

Though I contributed nothing, I got a great deal from these

seven years as a Clark trustee. Worcester is 45 minutes from

New York by plane, but those 45 minutes take you into

another America. Most of the trustees come from outside

Worcester: from the faculty of Radcliffe, from Florida, from

all over. I have never seen a group of people who work

together with such devotion and disinterestedness. Clark is

their cause; their work for Clark is the animating scruple

of their lives. At one meeting the choice of candidates for

honorary degrees was in progress. Dr. Jefferson reported

that several undergraduates had petitioned for Danny Kaye.

One of the trustees inquired: "Who is Danny Kaye?" In a time

when second-rate movie actors become instant statesmen, I

found this cultural lag on the part of my colleague

inspiriting.

The great project during the time I was there was the

building of a new library, the Goddard Library, named in

memory of Robert Hutchings Goddard, the pioneer in rocketry

who taught for a time at Clark. His widow is now a member of

the Board of Trustees. They hired a consultant, Keyes

Metcalf, the great library expert. He brought in a measuring

tape; he had measured the distances between chair and

reading table in many libraries, and he had a precise notion

of what that distance in the Goddard Library should be.

Another trustee, the wife of an important industrialist who

lives in Worcester (she is now chairman of the board) has

made the building of the library her pet project. She

describes herself as a housewife but she is a visionary. An

argument arose about the tables in a new dormitory. She

opted for wood, good solid oak or pine. Those who were for

vinyl or some sort of plastic objected to wood because the

students would carve their initials in it. "Let 'em carve,"

she said. She won her point, which, as I observed, was par

for the course.

Here in New York, when I get tied up in knots about

Vietnam—when a dinner guest, a charming and intelligent

university teacher, tells me that, after all, it is a small

war and I reply, with perhaps too much heat, that for those

who die in it it is as big as a war can be—I simmer down

after the guest leaves and it is soothing and reassuring to

think: "Well, up there in Worcester, they are measuring and

planning and building a library that will nourish

generations hopefully saner than ours."

A few years ago, in my mad, gay sixties, I began to work on

a book. I had (even then!) begun to brood over the past. I

made "a little list" of those I had known who were gone and

whom, had I the power, I would most like to resurrect. The

book was to be called: "Five I Miss." The five were: Chaim

Weizmann, Ernst Lubitsch, Harold Ross, George Gershwin,

Rudolph Kommer. The last was a singular character who was

deeply loved by a few people. Alexander Woollcott once wrote

a profile of him called "The Mysteries of Rudolpho." Kommer

came to New York as theatrical correspondent for the Vienna

Freie Presse. Later he became chef de cabinet for Max

Reinhardt and arranged his American tours. Him I have made a

leading character in my first and last novel. Kommer had his

cards printed:

RUDOLPH KOMMER

aus Czernowitz

He did this because Czernowitz, which was Rumanian from 1918

to 1940 and is now, as Chernovtsy, in the Ukrainian Soviet

Republic, had a reputation for venality so pervasive that

its citizens always pretended to be from somewhere else when

they traveled. It was his act of defiance.

I gave the book project up; I felt that it would take too

much research and run the danger of being too anecdotal. I

look over some of these anecdotes now—for George Gershwin,

singularly, in the week which Mayor Lindsay has designated

"Gershwin Week," a felicitous choice which justifies—if it

needed justification—my crucial vote for him. A night in

1926. I was walking up Broadway with George toward Child's

on 59th Street. The newspapers were black with screaming

headlines announcing the marriage of Irving Berlin and Ellin

Mackay. We were talking about it, everyone was talking about

it. George stopped, seized by a disturbing thought. He

looked at me with his candid brown eyes. "You know," he

said, "it's a bad thing for all song writers." I am a

collector of enigmatic remarks; I have never been able to

make out what this one meant. Could he have feared that

there would be a mass drive on the part of all song writers

to marry Ellin Mackays and that this would distract them

from their work?

I see an item, too, about Ira Gershwin—happily still with

us. He loved Coney Island. On a hot night, in August, about

midnight, he had a compulsive wish to see Coney Island. He

got a taxi and away we went. As we drove along the spangled

Elysium, Ira, gazing with happiness at the electrified

ferris wheel and chute-the-chute, made a large gesture. "My

Deauville!" he said.

With Harold Ross I came upon another enigma, which, at the

time, baffled both of us. It had to do with Ross's mother,

whom he brought from Aspen, Colo., and installed m an

apartment uptown. I never met her, but we heard a lot about

her. For one thing she rather sniffed at The New Yorker. She

demanded of her son why he wasn't on The Saturday Evening

Post. One day she called him up at the office in great

excitement. She was breathless. "Harold," she said, "I saw

the most beautiful theater in the world last night. You've

got to come with me. I'll go again just to show it to you."

There was no escaping. A dutiful son, Ross went and reported

to his friends. "The most beautiful theater in the world

turned out to be a Loew's movie house!" He loved to tell it

and his friends loved to listen.

On a Sunday not long after, I was invited to come out to

Sands Point by Nicholas Schenck, the eminence grise

of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer; he was known to the ranks as the

General. I arrived about noon and found the General at

breakfast and, to my delight, Ross sitting beside him. On

Ross's other side was Joseph Schenck, the General's brother.

We had coffee. Neither of the Schenck brothers was a snappy

conversationalist. There was a lull. I gave Ross bad advice.

"Tell them," I said, "about your mother and the most

beautiful theater in the world." Ross did. He didn't get

from the brothers the reaction to which he was accustomed.

There was a heavy silence; Ross saw that he had made a

gaffe. Finally, the General put his hand on Ross's arm and

spoke in a gentle, admonitory voice, as to an erring son:

"But, my dear Harold, do you know what we've spent to

redecorate that theater? Six hundred and seventy-five

thousand dollars! It is the most beautiful theater in the

world!"

With that the General and his brother got up and left. Ross

growled at me:

"For God's sake, will you tell me what the hell we've been

laughing at all this time?"

I reneged on "Five I Miss," but I am not quitting. I have

been reading Montaigne for many years and have a little

library about him and his times. I read, as they came out,

Donald M. Frame's lucid translations and, later, his

absorbing biography. Just the other day, in Andre Gide's

last book, "So Be It, or The Chips Are Down," I came upon

the following passage:

. . . We should particularly like to have, not so much

monologues of great men, even if they were Racine and

Pascal, as their conversations, discussions between

Montaigne and La Boétie, rambling conversations among

Racine, La Fontaine and Boileau or even with Father Bouhours,

like the interview, so wonderfully noted down, of Bernardin

de Saint-Pierre on a visit to Jean-Jacques. That is what

would really inform us. But everything sinks into the past,

even what we are taking care to note down today."

I have been wanting for a long time to write a play about

Montaigne. I shall have a try even at his conversation with

La Boétie. You couldn't write a play about Montaigne without

writing dialogues between him and his best friend. I shall

do this with the more security because Gide will never see

it. No one probably will ever see it because I am not

writing it for production nor even for publication. It will

serve to keep me in touch, for the rest, with a sane and

independent and civilized mind in a time of killing and

terror—like our own.

S. N. BEHRMAN has written, among plays, "Biography" and

"No Time for Comedy" and, among books, "Duveen" and "The

Worcester Account." |