|

|

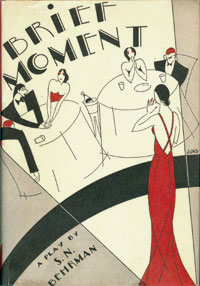

Brief Moment

S. N. Behrman

New York:

Farrar & Rinehart, 1931

First edition in dust jacket

Inscribed by Behrman |

| |

|

(On front free endpaper)

For my favorite trollope, Ida, / with

much love, / from Berrie / New York: Dec. 1931. |

|

|

Returning from Europe expressly for the

start of the production of Meteor, Behrman learned

that in a crush of despair Daniel Asher had committed

suicide. With the shocking death of his childhood mentor and

the general rejection of Meteor, the society standing

on the brink of the Great Depression, Behrman accepted his

first offer from Hollywood, at twelve hundred fifty dollars

a week. Moreover, Guthrie McClintic picked up the option to

Brief Moment (1931). As the decade drew to a close,

Behrman entered the most successfully productive ten years

of his career. Brief Moment returned Behrman to the

theatrical realm where everyone felt most comfortable with

him: wealthy people moving in an ambiance of high comedy.

Moreover, director McClintic pulled off the casting coup of

the season by offering the role of Harold Sigrift, Roderick

Deanís confidant, to the always astonishing, rapier-witted

Alexander Woollcott. By dint of determination, Abby Fane in

Brief Moment pulls herself up from an ignominous life

as a waitress in Pittsburgh, and becomes the darling of the

nightclub circuit in New York City, singing such blues as

Jerome Kernís "Bill." Millionaire playboy Roderick Dean,

whose wealth is inherited and consequently who flounders

about for a substantial and objective pursuit in life,

proposes marriage to Abby. She accepts, even though it is a

loveless partnership on her behalf. She now becomes the

darling of Cafe Society; invitations to her dinner parties

are eagerly sought. Former lover Cass Worthing returns to

her life, now that Abby is no longer attainable, and,

perhaps not surprisingly, she responds to his amorous

advances. This leads to divorce for the Deans and the

ultimate realization on Abbyís part that her substantial

love for Roderick crept up unawares during their marriage.

At the final curtain they are reconciled. Again, development

is less in the plot than in the slowly growing maturity of

the two leading characters, particularly Abby. By Behrmanís

own assessment, "The play ran though it didnít succeed."

This bantamweight comedy marks a watershed of Behrmanís

easement into the freedom of drawing-room comedy from the

restraint of comedy of manners. Brief Moment

straddles the line of demarcation, wavering more toward the

former than the latter. Imbued once again in the story of

the play are success/achievement, money, love, and marriage

as a business arrangement of convenience (as it appeared

with Clark Storey and Serena Blandish). An incompatibility

exists between father and son. His father is not present in

the text, but Roderick admits that he suffers the handicap

of a Protestant work ethic which an overbearing parent

instilled in him. Like many of his writer contemporaries in

the theatre and literature, Behrman here responds to the

intellectualís surety that a second American revolution

looms just beyond the horizon, a revolution that would

resemble Russiaís uprising, an imminent Red menace. Even

five years thence, the radical Dennis McCarthy brings down

the final curtain in End of Summer (1936) by assuring

the wealthy Leonie: "Donít worry about that [having her

wealth taken away] Ė come the Revolution Ė youíll have a

friend in high office." In Brief Moment, Roderick

assumes a most pessimistic outlook: "Who the hell am I to

strike an attitude? Tomorrow, I may be on a dole from a

Communist Government. Attitudes were all right when life was

stratified into castes and codes Ė but all thatís practical

these days is a kind of opportunism." (Three plays later,

End of Summerís Dr. Rice exemplifies just such

opportunism, and thirty-three years later, But For Whom

Charlieís titular Charles Taney revels in it.) While

change would have been in keeping with Behrmanís liberal

philosophy, his fear of how such change would severely alter

his own very comfortable life-style suggested second

thoughts to any overt action or encouragement on his part.

Yet social change remained an important feature in his work,

and late in life (1967) he became something of a political

activist: "80 Americans Urge U.S. to Seek Mideast Peace."

The New York Times listed Behrman as one of the

petitioners. |

|