|

|

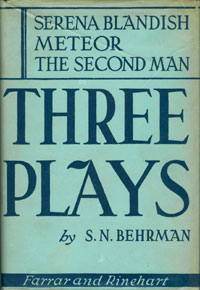

Three Plays

S. N. Behrman

New York:

Farrar & Rinehart, 1934

First edition in dust jacket

Inscribed by Behrman |

| |

|

(On front free endpaper)

For Sam Marx / My chieftain and /

friend. / From / S.N.B. / Hollywood: March, 1935.

First appearance of Serena

Blandish. Also includes Meteor and

The Second Man. Samuel Marx was the head of the

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer story department. |

|

|

Serena Blandish, which opened in New York in 1929,

presents a leading character emerging from an environment

somewhat similar to Clark Storeyís in The Second Man,

but one who achieves something of a reverse denouement. In a

Pygmalion-like situation, Serena follows her romantic

heart to find happiness. This idealism softens the razorís

edge of the sheer mercenary exemplified by Clark Storey; his

cynicism is blunted. Moreover, Serena Blandish begins

to substantiate areas of concern which will appear in all of

Behrmanís plays in varying degree: success (in the Horatio

Alger mold, which so captivated his childhood fancy),

wealth, love, and marriage. The first suggestion of a

conflict between generations, developed more fully in later

plays, particularly in The Talley Method (1941), I

Know My Love (1949), Lord Pengo (1962), and

But For Whom Charlie (1964), insinuates itself in the

peculiar father-son relationship of Martin and Edgar

Malleson. Tempering such conflict in Behrmanís oeuvre is his

endorsement of humane sensibility and tolerance. Serena

Blandish; or The Difficulty of Getting Married, a novel

written by "A Lady of Quality" (later revealed to be

Englandís Enid Bagnold) came to Behrmanís attention through

an associateís interest in the work. The novel suited the

playwright admirably, and it remained largely a problem of

finding a theatrically viable ending quite different from

the novel wherein Serena marries a Negro. Such an ending

Behrman determined as too inflammatory a resolution for the

late 1920s and not without reason. "That the play was to be

produced in a country where Negroes, often only merely

suspected of a crime, are dragged through the streets by

mobs of children and grown-ups and maltreated and burned

alive or lynched, gives me a legitimate defence of simple

and justifiable cowardice." The ingenuous Serena is a "good

sport," totally defenseless, and every man who comes along

exploits her. One afternoon Serena is swept up in a business

proposition: for a period of thirty days she will be

introduced to the wealthiest, most eligible bachelors in

London society. She is to capitalize on this arrangement and

to make a "suitable connection." The outcome is predictable

as Serena falls in love with a farthingless, low achiever,

Edgar Malleson (himself the designated predator of Princess

Vermouillť, from whom he later flees), and even he will not

marry Serena. Her unsullied naivetť still intact at the

completion of this experiment, Serena follows Edgar to the

Continent where he is to involve himself in a business

venture almost certain to fail. Although Serenaís penury

permits the playwright to manipulate her rather like a

puppet, she is still very much her own person and

represents, in the largest sense possible, the first of

Behrmanís independent females whose mature incarnations are

Biographyís Marion Froud (1932) and Lady Lael Wyngate

of Rain From Heaven. The other characters,

particularly the Countess Flor di Folio (who resembles an

erudite Mrs. Malaprop of Richard Brinsley Sheridanís The

Rivals) tend to fall into the archetypal

comedy-of-manners contour. Producer Jed Harris brought the

young Ruth Gordon to stardom as Serena. Her out-of-wedlock

pregnancy by Harris, recounted in Gordonís autobiography,

may offer an explanation for the abbreviated run. However,

its ninety-three performances alerted the Theatre Guild, who

had turned down first option on Behrmanís manuscript, to

re-evaluate their interest in the playwright. They

determined not to let his next offering pass them by. |

|