|

|

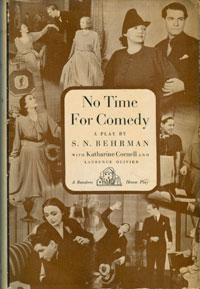

No

Time for Comedy

S. N. Behrman

New York:

Random House, 1939

First edition in dust jacket |

|

Whether Behrman’s disappointment over the

fiasco with the failed Wine of Choice prompted him to

transfer his loyalties away from the Theatre Guild must

remain conjecture. Joining the Playwrights’ Producing

Company as its fifth founding member assured him of greater

control with future productions of his, although that aspect

of the creative process never concerned him much. The

originators of the Playwrights’ Company, Robert E. Sherwood

and Elmer Rice, were adamant in their distaste for the

Theatre Guild’s production practices. The other two members

of Playwrights’ Company, Maxwell Anderson and Behrman’s

personal friend Sydney Howard, held similar views about the

Guild. Mainly they objected to producers Langner and Helburn

tampering with their texts, a phase of production and

preproduction that Behrman accepted as matter of course.

Reviewing the first matinee of End of Summer in

Boston, one critic observed: "Philip Moeller, Theresa

Helburn, Lee Simonson and others of the Theatre Guild staff

were buzzing around at the stage box to speak to the

players. I had the feeling that they were constantly

changing both the lines and the business. I know that this

is one of the best known theatrical sports, rewriting the

play every night after the show during the tryout weeks, and

playing a different version each day." Behrman’s new

alliance with the Playwrights’ Company did not prove to be

totally frictionless concerning practical measures. For

their first venture with Behrman, they found themselves

obliged to co-produce No Time For Comedy starring

Katharine Cornell – with whatever trepidations and lack of

enthusiasm – owing to previous agreements with that

manager/leading lady. Sole control over matters of

production provided a basic tenet of the Playwrights’

founding. This new joint association, however, constrained

them to cast Cornell as she made her first attempt at light

comedy – with a welcomed, surprising degree of personal

success. In No Time For Comedy, a seven-year itch

induced largely by a writer’s block infects playwright

Gaylord Esterbrook. In the presence, if not precisely the

arms, of "the other woman," Amanda, Gaylord’s writing

problem seems dispelled. Moreover, instead of permitting him

to write trivial comedies, where he displays unquestioned

mastery, Amanda inspires Gaylord to write a profound drama.

"Rot," thinks actress-wife Linda Esterbrook, somewhat out of

practical concern as she awaits the fourth of her husband’s

comedies as her next triumphant vehicle. (Her tolerance had

already forgiven him his assumed infidelity.) Better to

write successful trivial comedies than shallow tragedies.

Why not a comedy based on their own romantic triangle at a

time when the world is precariously perched on total chaos,

and her husband, masking his need for "experience" with a

kind of altruism, wants to run off to join the Spanish

insurgents? What better time for comedy than a period when

"The more inhuman the rest of the world the more human we.

The grosser and more cruel the others the more scrupulous,

the more fastidious, the more precisely just and delicate

we." Her justification? "One should keep in one’s own mind a

little clearing in the jungle of life. One must laugh."

Gaylord recognizes the wisdom of his wife’s reasoning and

prepares to write his latest comedy based on his experience

with Amanda. This successful offering has been regarded by

many as faintly autobiographical. This must remain a moot

point in the absence of any comments from Behrman, who

jealously guarded his private life. But he dedicated No

Time For Comedy to his wife, Elza. |

|